THE COST OF DEVELOPMENT: WHO PAYS THE PRICE?

Introduction: Development vs. Sustainability

Development does not come without a cost, but what is that cost, who bears it, and how much? While large-scale infrastructure projects drive economic growth and technological progress, they often disrupt local ecosystems and traditional water systems. The case of Perumal Puthukulam, a historic water tank in Tirunelveli district, Tamil Nadu, exemplifies this struggle.

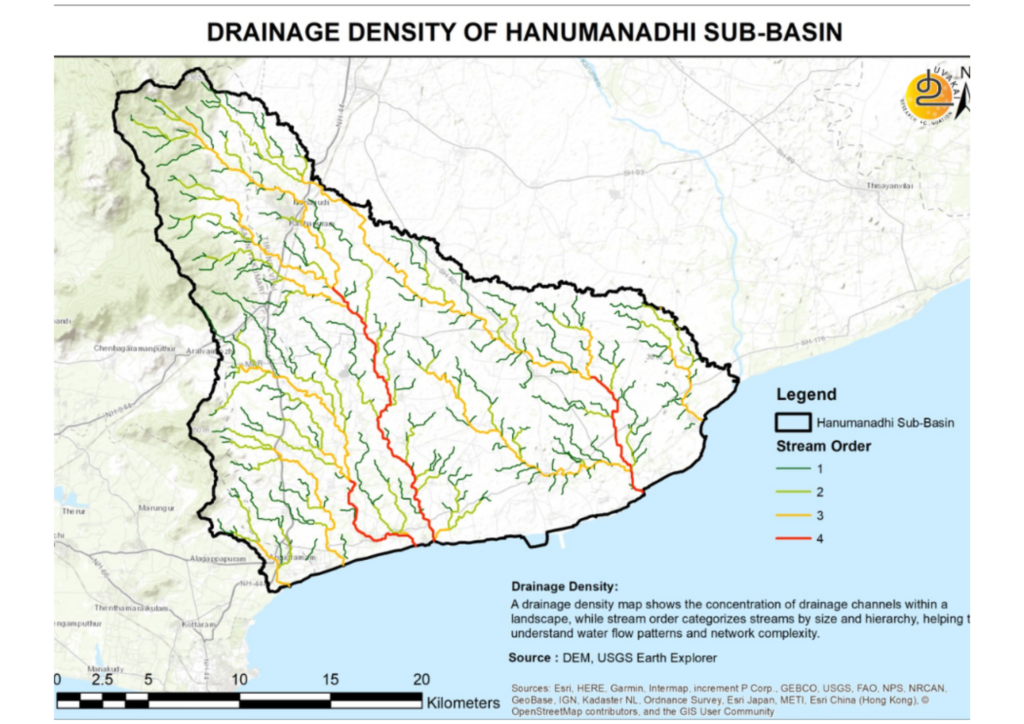

Location and Hydrological Context

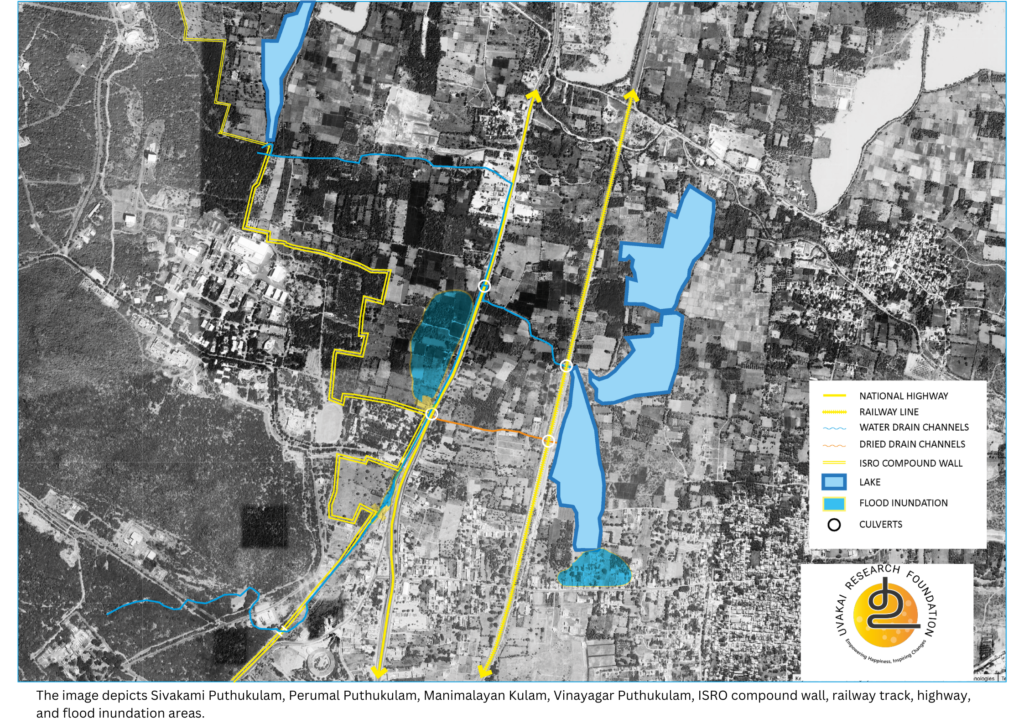

Perumal Puthukulam is one of the tanks within the Anuman Nathi sub-basin, part of the Suravazhi Odai cluster. It receives its water from Mahendragiri hills, located in the Western Ghats near Kavalkinaru, Tirunelveli district. This is a crucial hydrological region, as it marks the point where the Western Ghats turn northward, creating a rain shadow effect over the Radhapuram region. Consequently, Radhapuram falls under the overexploited Nambiyaru Basin, making tanks like Perumal Puthukulam essential for water security.

Perumal Puthukulam is located within Perungudi Village II, Radhapuram Taluk, covering:

- Total area: 17.73.50 hectares

- Ayacut area (irrigated land it supports): 15.40.50 hectares

- Storage capacity: 2.49 million cubic feet (mcft)

Despite its importance, the tank has struggled to receive water for over three decades due to multiple barriers created by infrastructure projects. The barriers are listed below.

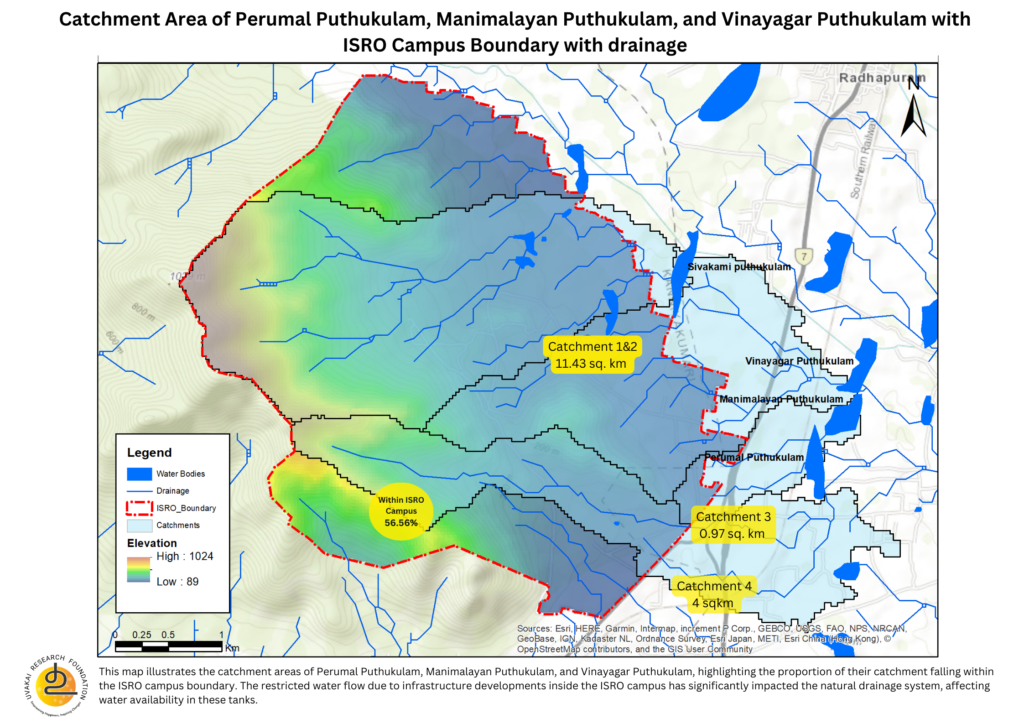

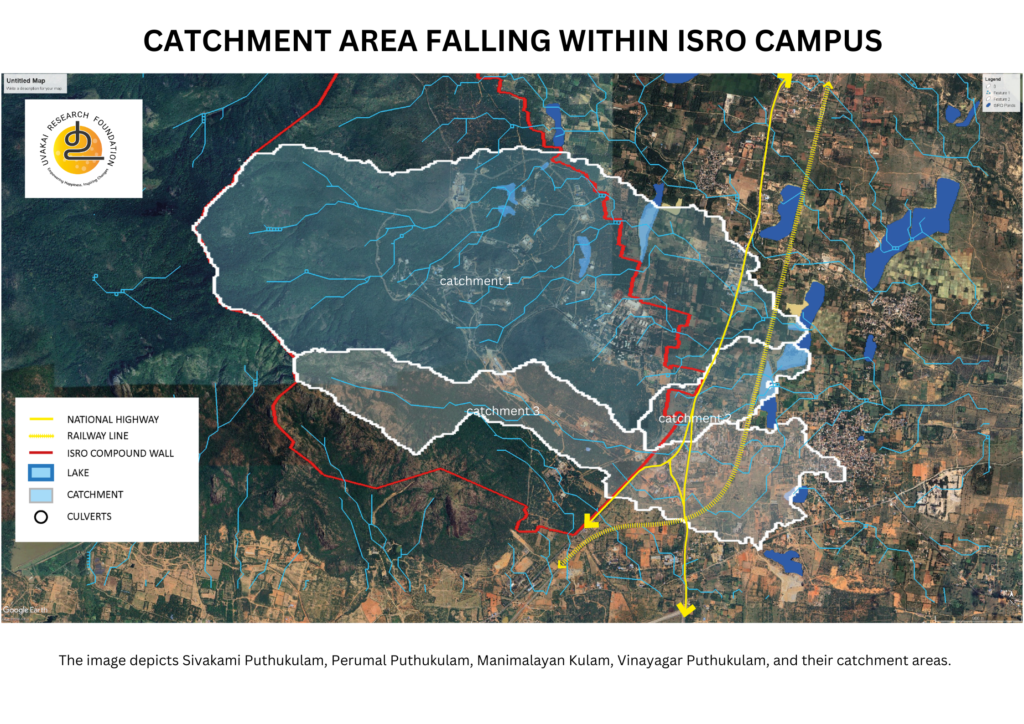

Barrier 1: ISRO’s Fencing and Restricted Catchment

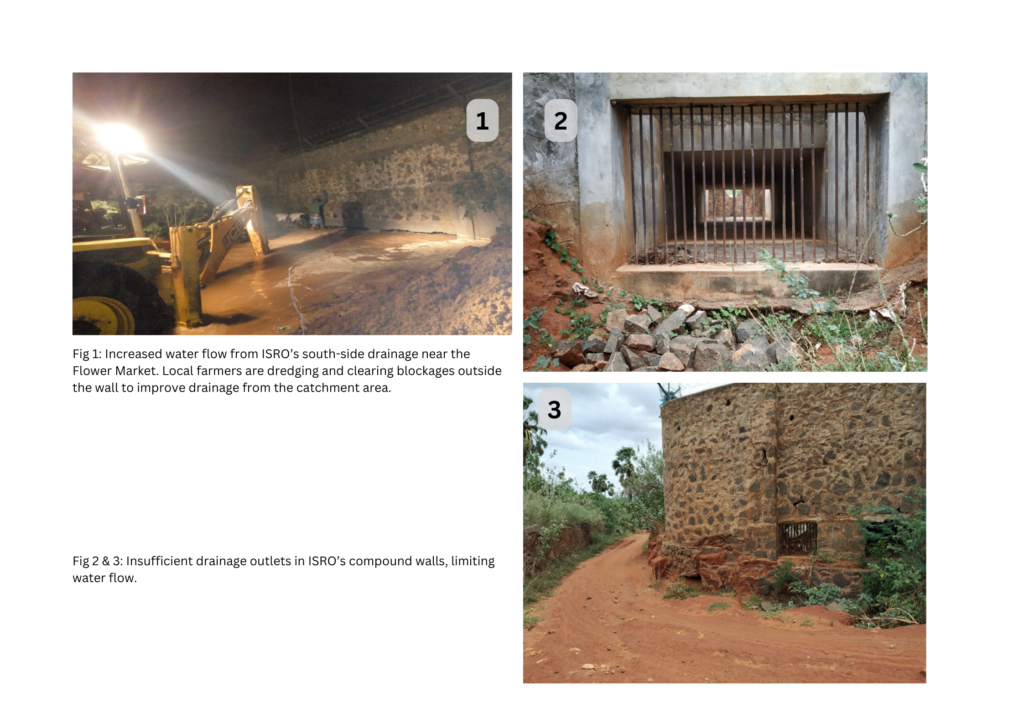

More than 56.56% of Perumal Puthukulam’s catchment area lies within the ISRO Mahendragiri campus. While a few small outlets allow water to flow out, their size and number are inadequate to sustain the downstream system. Additionally, internal roads, check dams, and baby ponds within the ISRO campus further disrupt the natural drainage pattern, holding back crucial water that should flow into Perumal Puthukulam.

Barrier 2: National Highway Blockage

The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) failed to conduct a proper catchment analysis before constructing the highway. As a result, the highway acts as a barrier, preventing water from reaching Perumal Puthukulam. A culvert could have been constructed to facilitate water flow, but this was overlooked.

Barrier 3: Southern Railway Track

The Southern Railway line cuts across the drainage path, further restricting the natural movement of water. However, in contrast to NHAI, Southern Railway has constructed two culverts, allowing some water to flow toward Perumal Puthukulam. But without upstream connectivity, these culverts remain underutilized.

Barrier 4: Poorly Designed Drainage Structures

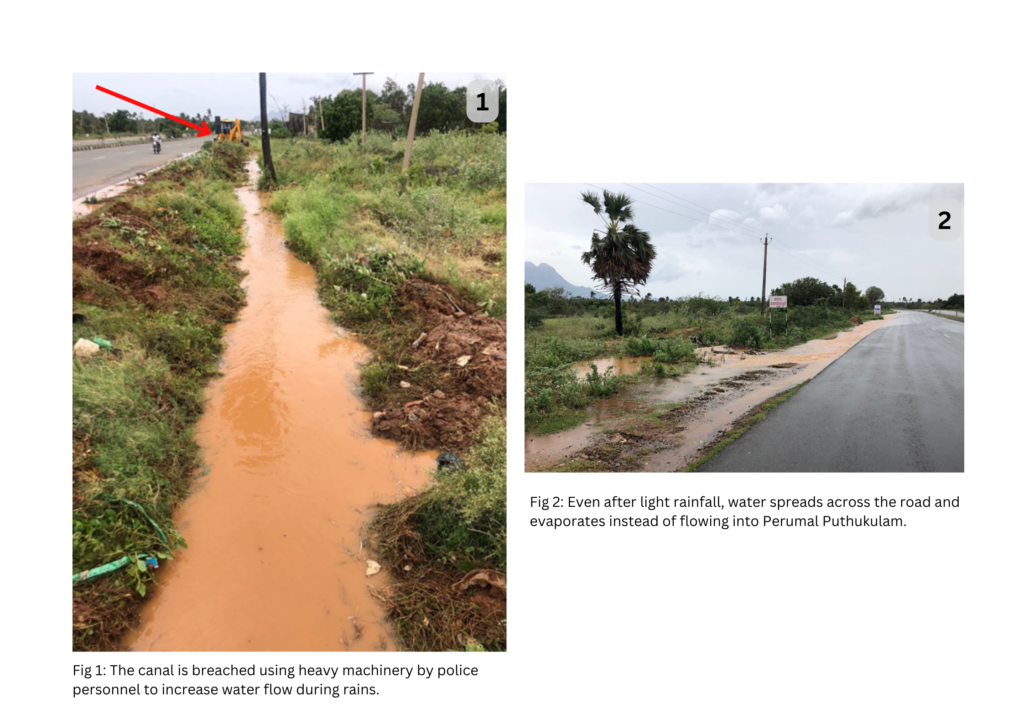

As water emerges from ISRO’s small outlets, it initially reaches the Perumal Puthukulam Odai (a natural drainage stream) near the IPRC compound wall. Here, additional water from Kavalkinaru Junction joins, increasing the flow volume. However, the covered canal near IPRC entrance is too small, causing water to spread over roads and fields instead of reaching Perumal Puthukulam.

Even during the monsoon season, water does not reach the tank effectively. Local authorities, including the police department, frequently break bunds and lining walls to release excess floodwaters, but this is a temporary and damaging solution, harming farmland and water infrastructure.

Barrier 5: A Shrinking Waterway

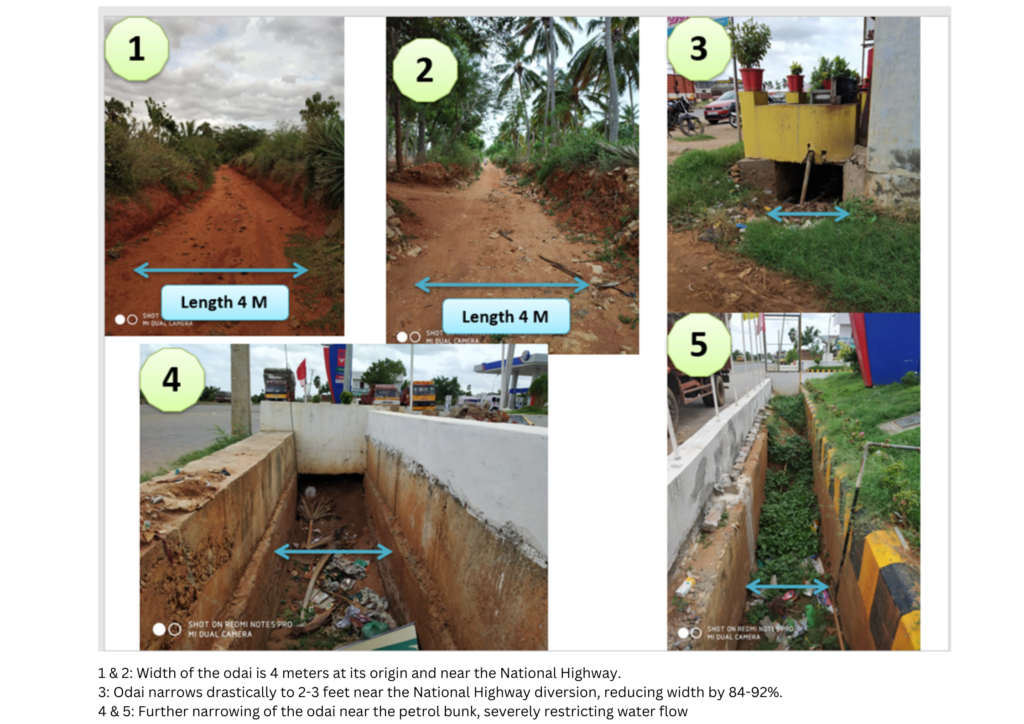

While the water from the southern catchment struggles to cross four barriers, the northern flow exiting the ISRO catchment near Sivakami Puthukulam initially follows a well-defined waterway. This channel, which carries water only during rains, also serves as a transit route for transporting vegetables and crops from nearby farmlands.

However, as this wide mud road approaches the National Highway, it turns southward, aiming to reach Perumal Puthukulam by passing under the NHAI bridge. At this crucial juncture, unregulated commercial development—including hotels, petrol bunks, and other establishments—has drastically reduced the waterway to just one-tenth of its original width. This constriction disrupts the natural flow, causing water to spill onto roads and fields instead of reaching Perumal Puthukulam in time, leading to significant wastage.

Barrier 6: Declining Water Flow and the Breakdown of Water Management Between ISRO and Local Communities

Over the years, the water flow from the catchment area has significantly declined. In the northern catchment, very little water now exits the ISRO compound, as multiple small ponds have been dredged within the campus at key drainage points. On the southern side, where one of the largest drainage channels exists, ISRO has constructed three check dams and a small pond, further restricting the natural outflow.

Historically, breaches in the compound wall led to flooding, but instead of restoring the natural flow, internal water retention measures have altered the drainage dynamics. These changes are evident on Google Maps. Surprisingly, rather than taking steps to support nearby villages as part of its CSR efforts or working to balance the disrupted ecosystem, ISRO denies implementing water retention measures within its campus.

According to local farmers, there was once a liaison system in place to coordinate water management, including the cleaning of waterways before and after every monsoon. However, at present, there is no communication mechanism between local farmers, the Water Users Association, and ISRO authorities.

Neglected Reforestation: A Missed Opportunity

This region was once under the Forest Department before being handed over for ISRO’s development. Over the past five decades, extensive infrastructure expansion has led to significant forest loss. However, neither ISRO nor the Forest Department has taken substantial steps toward afforestation to compensate for the lost green cover. This failure has further contributed to declining rainfall in the area. Additionally, the absence of a rain gauge station makes it difficult to assess long-term trends in precipitation, highlighting the lack of proactive environmental monitoring and restoration efforts.

Conclusion: Can Convergence and Reforestation Save Perumal Puthukulam?

This case highlights the failure of convergence among multiple stakeholders—ISRO, NHAI, Southern Railway, Forest Department and local authorities—in ensuring water security for local communities. Despite national discussions on integrated water resource management, coordination among agencies remains weak on the ground.

The question remains: Will Perumal Puthukulam regain its role as a lifeline for Radhapuram’s farmers before the next monsoon, or will the struggle for water continue?

Simple yet critical interventions—constructing culverts, restoring drainage pathways, and reviving coordination among stakeholders—can help restore the tank’s functionality. Additionally, reforestation efforts are essential to address long-term water security and mitigate declining rainfall. For five decades, no significant afforestation measures have been undertaken to compensate for forest loss due to infrastructure development. A concerted effort from ISRO, the Forest Department, and local authorities is necessary to restore ecological balance.

The path forward is clear, but the real question is: Who will take responsibility? Will development projects continue to overlook the environmental cost paid by local communities and ecosystems, or will a collaborative approach finally emerge?