Introduction

The Chennai River Basin, covering 4,959.1 square kilometers in North Tamil Nadu, drains into the Bay of Bengal through four major rivers: the Araniar, Korattalaiyar (Kosasthalaiyar), Cooum, and Adyar. Unlike other sub-basins, the Kovalam sub-basin, which spans about 812 square kilometers, doesn’t form a river. Instead, it drains water through low-lying land that creates marshes and backwaters, eventually discharging at Kovalam.

The Kovalam Basin is divided into five catchments. The northern catchments fall within Chennai’s metropolitan area (CMA) and drain into the Pallikaranai Marsh, which discharges water into the sea via the Buckingham Canal. The southern catchments drain into the Great Saltwater Lake, which also eventually discharges into the sea at Kovalam and Ediyur.

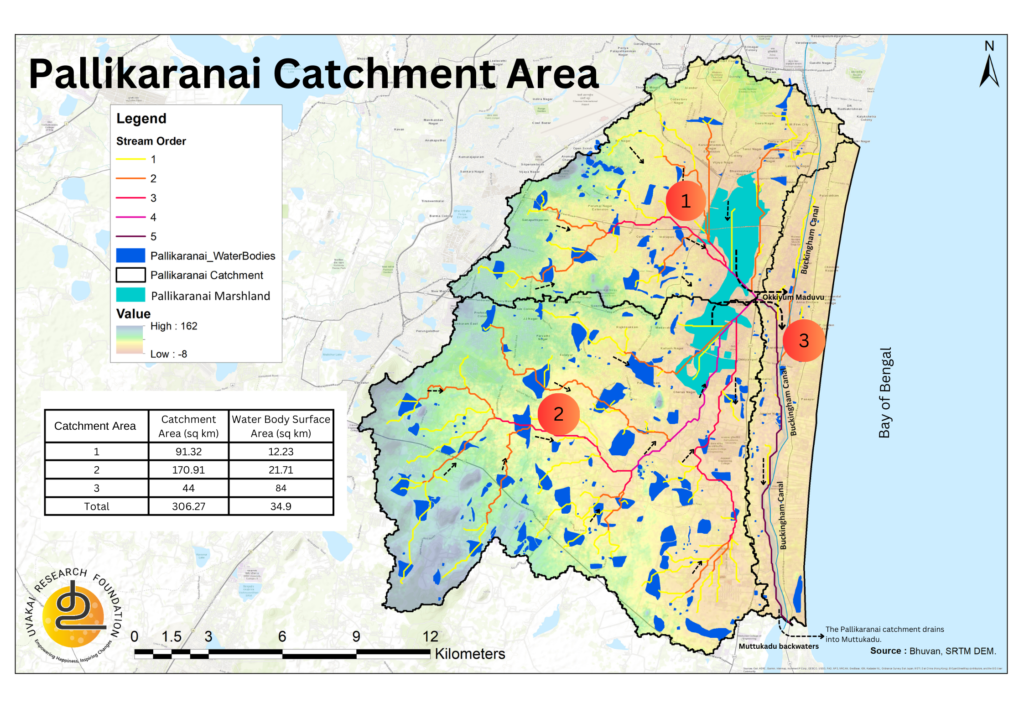

Geography of Pallikaranai Catchment.

The Pallikaranai catchment spans 306.27 square kilometers and is home to over 317 water bodies, including 63 lakes larger than 10 hectares. These contribute to the region’s hydrological balance. The pallikaranai catchment can be divided into 3 smaller catchments. The upper and the lower catchment drains into into Pallikaranai Marsh, one of Chennai’s last remaining natural wetlands, covering 694 hectares and the third part drains directly into the Buckingham canal. The marsh is ecologically vital, playing a significant role in the region’s water availability and flood mitigation. The marsh is recognized as a Reserve Forest under Section 16 of the Tamil Nadu Forest Act of 1882 and is also designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance on April 8, 2022, with the Ramsar Site Number 2481.

Function of Pallikaranai Marsh

Located below sea level, Pallikaranai Marsh acts as a natural reservoir, storing water before it drains into the sea. This storage helps maintain the groundwater table during dry periods, supporting the region’s water needs. Currently, the marsh can hold 5-6 million cubic meters of water, assuming an average depth of 1 meter.

Water drains through Okkiyum Maduvu, a natural check dam, and into the Buckingham Canal, which is the marsh’s only exit point. From there, the water flows to the sea at Kovalam.

The Role of Buckingham Canal

Constructed in the early 1900s, the Buckingham Canal runs parallel to the Coromandel Coast. Originally built for navigation, it now serves a crucial role in flood mitigation for the Pallikaranai Basin, draining excess water from the marsh over 13 kilometers to the Muttukadu backwaters. However, the canal’s low natural gradient and narrow width slow the drainage process, causing delays in discharging water, especially during heavy rainfall.

Impact of Urbanization

Urbanization has significantly altered the natural hydrology of the Pallikaranai catchment. With around 80% of the catchment area now urbanized, the land’s capacity to absorb rainfall has been greatly reduced. Concrete stormwater drains now channel surface runoff directly into the marsh, further stressing its limited storage capacity. During heavy rainfall events, such as a 20 cm downpour, the volume of water entering the marsh can be up to 10 times greater than its capacity, leading to inundation of nearby areas.

Flood Risk and Vulnerability

The slow drainage of water through the Buckingham Canal, combined with the reduced infiltration capacity of the surrounding urbanized land, makes neighborhoods near the Pallikaranai Marsh highly vulnerable to flooding. Areas like Perungudi, Sholinganallur, Velachery, and the Chennai IT corridor, located in low-lying areas, are particularly susceptible to flooding during monsoon rains.

Recommendations to Protect the Marsh and Reduce Flooding

- Widen the Buckingham Canal: Increasing the width of the canal would enhance water flow, allowing for faster drainage and reducing flood risks.

- Prevent Further Urbanization: Strict regulations should be enforced to stop land reclamation and encroachments around the marsh.

- Desilt and Restore Water Bodies: Removing silt from the region’s lakes and ponds will enhance their water-holding capacity, reducing the amount of water entering the marsh.

- Remove Encroachments: Clearing illegal structures around the marsh will restore its natural boundaries and functionality.

- Improve Basin Drainage Management: To reduce surface runoff, more infiltration infrastructure should be created. Augmenting existing stormwater drains with infiltration interventions will create a hybrid system that combines both drainage and groundwater recharge, mitigating the impact of heavy rains.

Conclusion

Pallikaranai Marsh plays a vital role in managing the hydrology of the Kovalam Basin and mitigating flooding in surrounding urban areas. However, rapid urbanization, encroachments, and reduced infiltration capacity have strained the marsh’s ability to manage stormwater, increasing the risk of flooding in nearby neighborhoods.

To address these challenges, it is crucial to implement a multi-pronged approach to improve the resilience of the Pallikaranai catchment and protect vulnerable communities from future flooding events.

Ar. Udhayarajan,

Director,

Uvakai Research Foundation

Udhay@uvakai.org